MYRIAM BOULOS – OVEREXPOSED

MYRIAM BOULOS – OVEREXPOSED

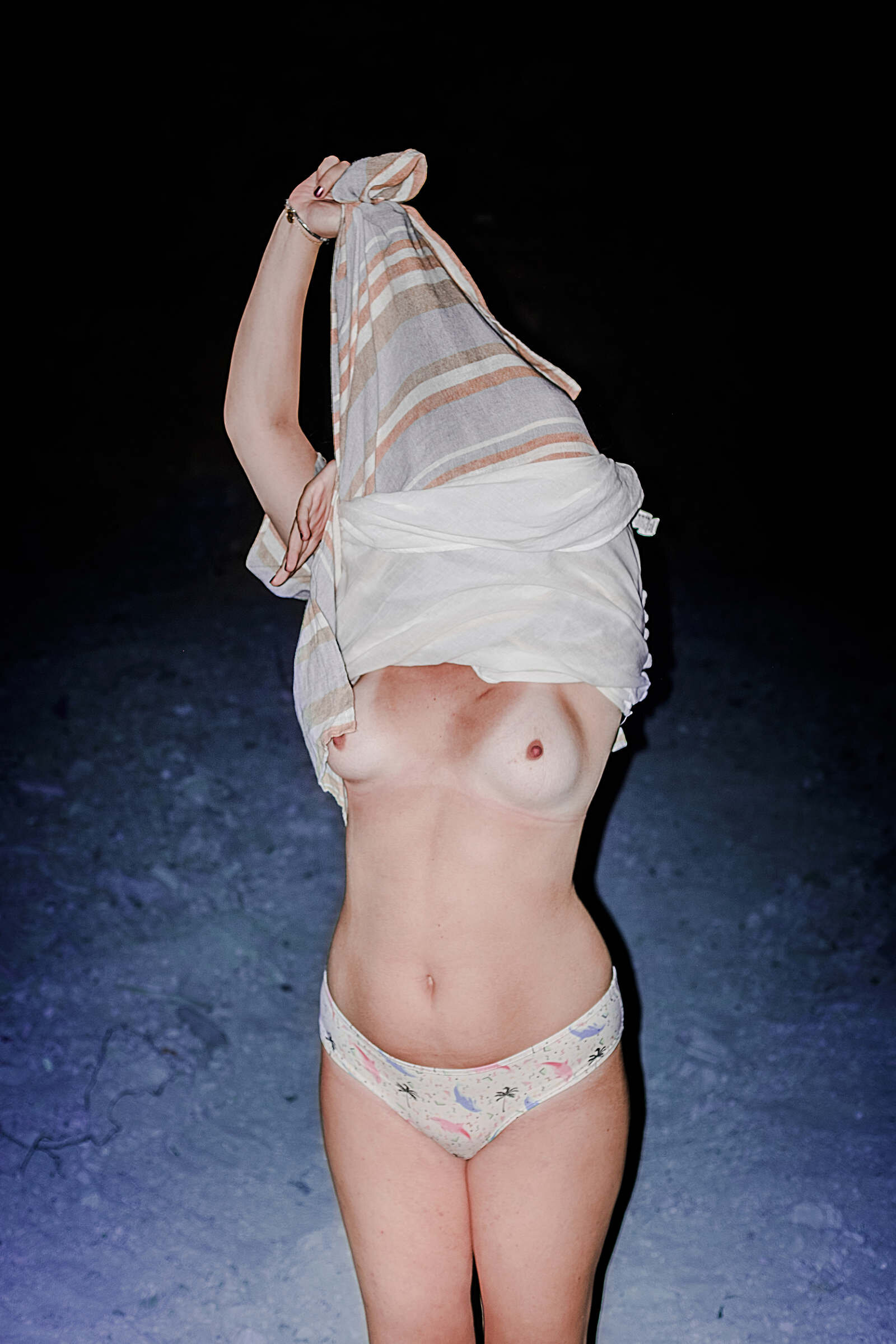

Although Myriam Boulos’ lens seems purely observational, her mission to shed light on the marginalized and the misunderstood by means of overexposure positions her not only as a notorious Lebanese photographer, but also as an activist. Bold, daring, and hopelessly romantic, her images consistently strike a sensitive chord as she forces society to look at itself in the mirror when it would rather look away.

How would you define yourself as an artist?

I don’t really do the difference between the person and the artist, and I am really bad at defining things! I guess I would say that most of the time I feel a little alien…

Your work is often in relation to Beirut. What’s your relationship with your home town?

I started photography when I was 16. At the time, I was beginning to discover both Beirut and my body as a young woman. I used to go to the conservatory after school, and on the way, I would get lost in the city with my camera. My camera always helped me get out of my little bubble and discover my surroundings which was back then, and still is, Beirut’s fragmented and contradictory social map. As weird as it sounds, I have always felt a deep connection between the city and the body I live in.

You say the relationship between your body and the city has been intertwined since you are 16. How has that relationship evolved today?

I have almost always felt like a stranger in my city and in my body. I think that my activism is bringing me closer to both. (And I do this mainly through photography.)

You often play with themes of body acceptance, patriarchy, identity… how do you go about choosing your themes?

Actually, photography is linked to my personal life. I take a lot of pictures in the moment, and it’s only in retrospect that I realize what I was looking for and obsessing about at the time. The themes impose themselves on me. It is more a question of need and necessity than a question of desire or choice.

You play a lot with exposure, namely, overexposure, which adds a raw quality to your work. What would you like to expose as an artist for the world to see?

I try to question things that are normalized in society. I guess it is one of the reasons I have this need to use the direct flash: to put light on some things that are always here but we are taught to ignore.

Being in the revolution is emotionally and physically draining by itself. I think that photography makes it easier for me to process things.

What are some of the things that society ignores that you insist on shedding light on and why?

Patriarchy, Kafala (an exploitative system used to monitor migrant workers in Lebanon), the abusive relationship we have been trapped by the current system in Lebanon. Honestly when I put words on these things I feel like a victim. And when I take pictures I feel like I am acting on things (In my own way of course not saying that I am changing the world!).

Your subjects are so vulnerable and portrayed in very intimate ways. How do you get them to bare it all, inside and out, without being invasive?

I think it is a matter of respect and being conscious of the other.

In the fall of 2019, the people of Lebanon started a massive uprising against the government. Having been on the streets myself, I’ve observed you documenting the protests, even when it got heated. What’s it like documenting an uprising while in the midst of it?

For me, photography is my way of participating in life and it is my way of taking part in the revolution. When the revolution started, it was the most natural thing for me to take my camera and go to the streets. It is not the photography part that is hard. Being in the revolution is emotionally and physically draining by itself. I think that photography makes it easier for me to process things.

What’s it like focusing on the details in a context where you have to be fully aware of your surroundings for your own safety?

I don’t know if I have an answer to this question... but in a way, I always have this (stupid) feeling that my camera keeps me safe. I am definitely delusional. But yeah I don’t have an answer. Things happen. I react. We have to. Also, I am very scared at many moments. Here’s a mini text I wrote after one of the violent nights:

“Monday, 20 Jan, Beirut, Lebanon

Tonight, in the teargas, I took all my pictures with my eyes closed.

They say the moment of a picture is a black out.

I wonder, if I don’t look at these emotions, will they disappear?”

“I have almost always felt like a stranger in my city and in my body. I think that my activism is bringing me closer to both. ”

Has your work ever made you feel unsafe?

Sharing my work automatically and necessarily put me in a vulnerable and unsafe position. I felt particularly unsafe at the beginning of the revolution when I got bullied and shamed because of my pictures.

When Times Magazine shared your photographs of the revolution, you were the subject of huge social media backlash. Some people felt like they were vulgarizing the movement. What’s it like being on the receiving end of social media backlash, and how did you deal with it?

The backlash was a nightmare and I stopped taking pictures during a week because the cyber bullying was too violent. I even stopped eating which has never happened to me. After a week of endless personal messages like "Marida nafsiyyan" (mentally ill), "you should kill yourself", "chlikkeh" (whore), "kalbeh" (bitch), etc. I took my camera and went back to the streets. I never could’ve done it without my family and my friends and all the messages of support that’s for sure. I honestly don't know what are the best ways to make a change in this world but bullying shaming and intimidating are definitely not the answer. Conclusion: BULLYING SHOULDN'T BE NORMALIZED.

Can you contextualize what the backlash was about?

Some people said that my pictures did not represent “us”, us referring to our Lebanese society. Lebanon is so fragmented and contradictory that I personally have trouble grasping what "us" refers to. Some of my pictures show the violence of the revolution. Many people, those who criticized me, couldn’t deal with this part of the revolution and for so many reasons they did not want it out, they did not want the image of their revolution and their country to be associated with violence. As much as I can understand where this comes from, for me it is important to listen to all the different means of expression and violence is definitely one of them. For instance, fire and broken glass speak to me as much as well-articulated messages. I believe that the backlash highlighted classism issues.

Your work has vivid social-political commentary by means of your subjects and the context you shoot them in, but your lens still manages to seem purely observational. Is this intentional?

Maybe because I don’t know anything; and I just feel and question things?

What’s next for Myriam Boulos?

Lebanon is drowning in misery but I can't imagine myself leaving the country.

It's like some plants cannot be transferred to a different pot. I don't know. Surviving and living I guess? And after this long confinement phase due to Covid19, I have a huge desire to take pictures of life, in all its forms.

Interviewed by Ralph Arida