ARNOUT VAN ALBADA - THE MONUMENTAL BEAUTY OF A PUDDING

THE MONUMENTAL BEAUTY OF A PUDDING

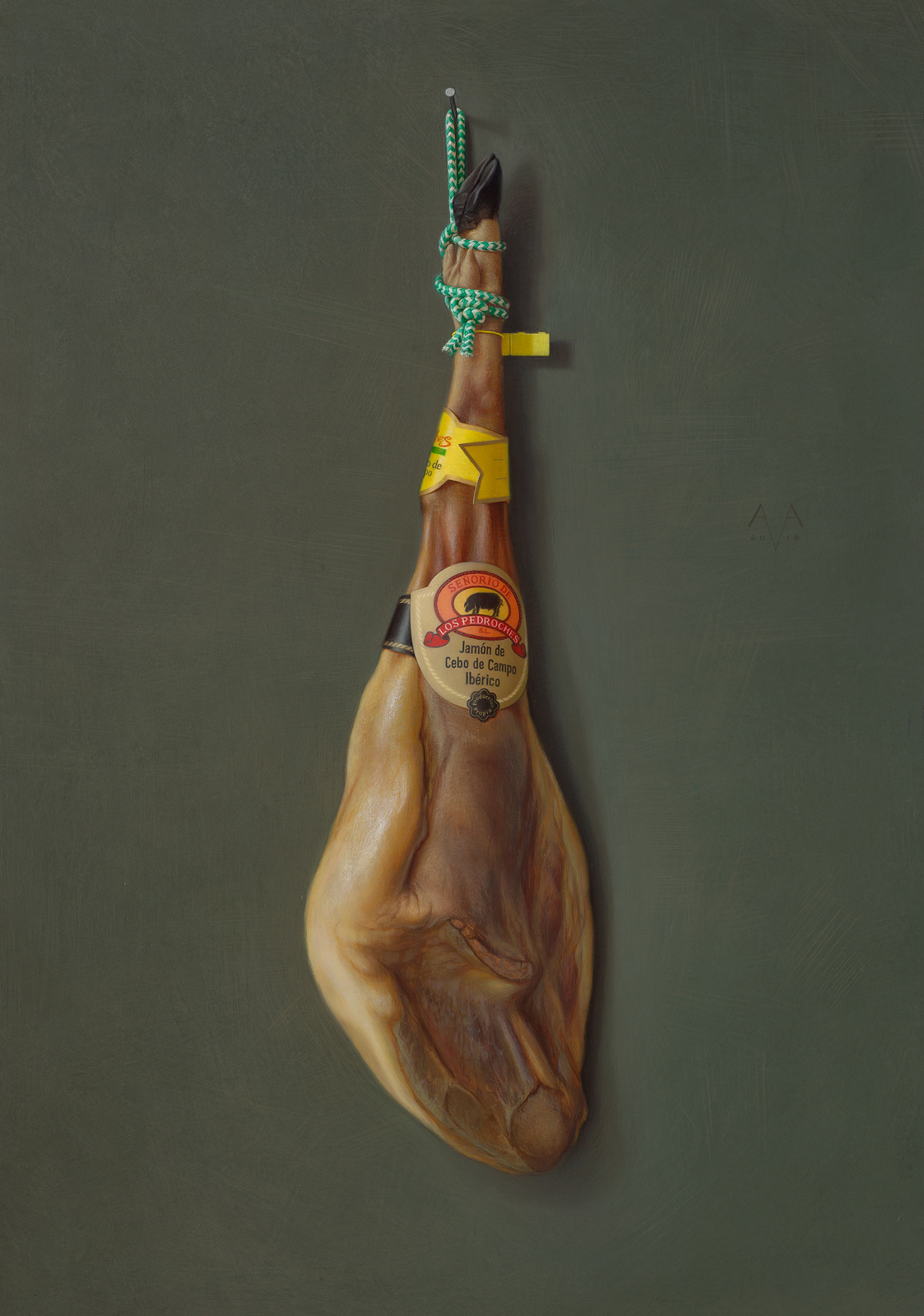

Arnout van Albada’s studio is his kitchen. Quite literally at times, for the Dutch artist loves his food and loves to paint food, anything from raw vegetables and Spanish hams to sardines and cream cakes. In the history of art, food is a well known symbol of the “vanity of vanities” the simple truth that all creation must perish. However, more than rubbing our noses in deeper meanings, Van Albada aims to convey the monumental beauty of such a simple food item as fennel or a pudding. And he does so with such a photographic eye for detail, that it really makes you want to have a bite …

Arnout, has drawing been a passion for as long as you can remember?

Yes, ever since I was a small child it was my favorite pastime.

What did you like to draw as a child and/ or teenager?

As a child I would draw anything I had seen that fascinated or impressed me: ‘Jesus crucified’ after visiting late medieval churches in Italy; firemen and fire trucks after watching a fire near our house (which scared me); a skating contest on TV; portraits of family members; and lots and lots of soldiers and crashing aircrafts due to a WWII obsession. Later on, as a punk rock inspired teenager, I mainly drew scary and depressing cartoon-like figures.

When did you realize you wanted to make art a professional career?

At first, I wanted to become an illustrator or graphic designer. Yet, once taking courses at art school it all seemed a bit boring to me. On the other hand, I loved my classes in figure drawing and painting a lot, later followed by still life painting, so I continued in that direction.

What did you study?

Drawing and painting at the Minerva Academy in Groningen in The Netherlands.

Were your parents supportive of that choice?

Yes, they were. And I think they were especially happy I chose something that I liked doing, especially after high school, which I did not like a lot. They have always been supportive – until this very day.

You have this amazing, almost photographic technique. Can you tell us a bit more about how a painting comes to life?

I paint on panel. I start with a monochrome (red/white) underpainting, using egg tempera. Then I work out the composition and shapes until I am satisfied. I continue by creating several layers using (semi-) transparent oil paints.

The underpainting, however, continues to shine through locally, which offers a wonderful depth and richness of color and texture, despite the fact it is all painted quite thinly. Only occasionally I apply oil paint with thicker brushstrokes. Finally, I use glazes to optimize color and tone.

You often paint foods and sweets. Why is that?

I love good food. I think you need to be in love with your subject to make a good work of art. In food, and in its packaging, often subtle contrasts in textures, colors and shapes can be found. Take the dull gray-ish exterior of a salami and its colorful juicy interior. Or soft velvety raspberries in a shiny black plastic box.

Due to the transitory nature of food items, there is a sense of urgency to capture their beautiful contrasts before they change or disappear. I try to catch the elusiveness of an object, isolated from its context, to create a timeless and magical image.

Do you have a sweet tooth?

Not particularly. I do like sweet stuff, such as a piece of chocolate with my coffee or a good pastry or a nice dessert after dinner, but I’m not munching sweets or cookies in between meals.

“I think you need to be in love with your subject to make a good work of art.”

In the early nineties I had a Dutch friend whose father was a painter. He always complained that there was no longer any love for traditional craftsmanship at the art academy and in the world of art in general. Do you agree?

I am afraid I have to agree with him. When I was a student, the Minerva Academy was considered a last refuge for people who wanted to learn to draw and paint nature. The so called “old school” methods had already been abolished at other academies. But despite increasing outside pressure Minerva kept offering classes in classical painting and drawing methods.

As students, we spent many, many hours practicing nude figure drawing with charcoal and oil paint. However, shortly after I graduated things changed. More and more easels at Minerva were thrown out and painting classes turned into talking sessions.

I think the result of this development can be seen in museums and galleries today. Conceptual art is still dominating and (digital) photography has taken over the ‘realism’ of traditional painting, which I do not necessarily consider a bad thing by the way.

Maybe the worst consequence of this evolution is an inability among art critics to recognize a well-made work of art from a lesser one. Their observations have become more superficial. They often lean on international trends. These days, the art world is dominated by, on the one hand, works that overwhelm or shock the crowds and, on the other, by art that is totally incomprehensible and elitist. What lies in between, and which often contains the real gems, in my opinion, is often overlooked.

Was it hard sometimes at the academy, being in a climate dominated by conceptual art?

Certainly. Even though the regime officially ended, it was an interesting time. There was always debate. Some students were quite fanatic, others mild. The academy itself was divided. In the second year we were able to choose between teachers who taught classical methods or those who were into modern and conceptual art. In the third year it was possible to choose any teacher you wanted. Every combination was allowed, which lead to serious arguing among teachers, as they tried to save their students from what they saw as certain artistic misery. At times it was hilarious. Once the ‘old school’ teachers had retired, one could say that the conceptual artists had won the battle.

Is realistic art making a comeback these days?

It sure is! But it has still not fully integrated into the ‘official’ art world. With the exceptions of photography and, to a lesser extent, photorealistic painting, art critics, galleries and museums for decades have mainly been focused on conceptual and non-figurative abstract art. This has resulted in a shortfall in expertise on realistic art. Retrieving that expertise will be a whole lot easier said than done.

What artists do you admire? Who would you name as influences? Do they all go back to the 16 and 17th centuries? Or do you have some contemporary preferences as well?

Some go back to the early Italian renaissance: Piero della Francesca, for example, or Mantegna. They look at their subject almost like an architect, which I love to do myself. But I also love 17th century still life painters, such as Adriaen Coorte, 18th century painters like Chardin, American realists Wayne Thiebaud and Andrew Wyeth and many others.

If you could have any three paintings anywhere in the world, which ones would you like to have?

Only three is a very hard choice. And my answer will probably be subject to change every once in a while. I love Asparagus by Adriaen Coorte and Chardin’s La Brioche. And at this very moment my third choice would be Richard Diebenkorn’s Cityscape I. It is from 1963. It’s not a still life, but such a perfect mix of abstract and figurative painting, with a great rhythm in tone and colour.

What are you currently working on?

There is always food-related stuff in my studio, but at the moment I am making a side-trip to medical supplies. Surgical gloves on a sea-green cloth, and gauze bandage on a stainless steel surface ...

If you were not an artist, what would you have liked to be?

A surgeon or chef.

INTERVIEWED BY PETER SPEETJENS