FEATURE: MEL RAMOS - FORBIDDEN FRUITS OF PIN-UP

THE FORBIDDEN FRUITS OF PIN-UP KING MEL RAMOS

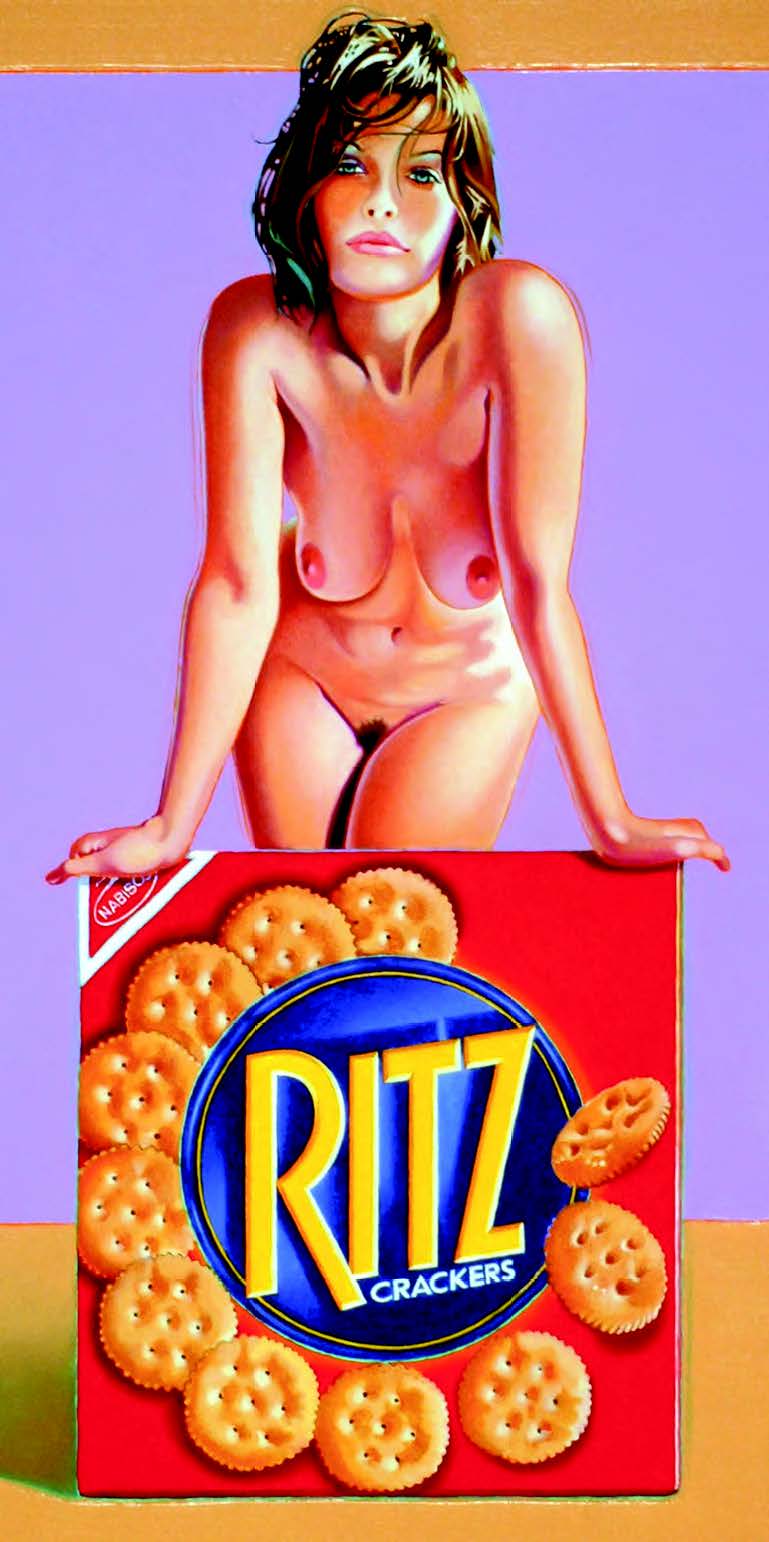

InspIred by comIc books and the all amerIcan art of pin-up, Mel Ramos’ work Is at once a celebratIon of the female form and a playful crItIque on the Increased use and sexualizatIon of women In ads and publIcIty sInce the 1960S.

When a gallery in the city of Cologne in 1967 staged a Mel Ramos exhibition, German police officers decided to storm the place to cover the paintings with white sheets to “protect the innocent.” Thus they unwillingly produced a defining moment in the history of 20th century art, according to Daniel Schreiber, who as a curator at Germany’s Tuebingen Kunsthalle recently organized a major retrospective of Ramos’ work.

When we see Ramos’ work today, we can hardly understand what the big fuzz was about. Schreider compared it to Edouard Manet’s 19th century painting “Lunch on the Grass,” which shows a naked woman having a picnic with two men in suits. While the painting looks rather sweet and innocent, it produced a huge scandal at the time, even though it only insinuates that the lunch on the grass was about more than just eating.

The Cologne police “performance” helps us understand why Ramos’ work is particularly popular in Germany. After all: what better publicity than a ban? Tell a person he cannot see something and he will do anything to have a peek – certainly in the case of Ramos’ sweet forbidden fruits.

Born in 1935 in Sacramento, California, Ramos is one of the earliest and one of the least well known representatives of the Pop Art movement. He is also one of the few still alive and one of the few based on the American west coast. Ramos is definitely the sexiest of American Pop Artists. Ramos’ pin-up girls are being served “at your service” in a James Bond Martini glass, pop out of pineapples, melons and candy bars, smile from behind bottles or suggestively ride giant Havana cigars.

More recent work such as the “Transfiguration Series” offers more perfectly shaped ladies, this time being born out of classic Greek or Roman statues, in a way reminding us that women and nudity has caught artists’ attention throughout the ages. However, his work is first of all fun and entertaining. “I have to continue with the idea of humor,” Ramos once said. “Everything else is so depressing. Life is so depressing. Everybody’s being shot.”

It may be obvious that Ramos’ art is greatly influenced by the world of advertising, as he often depicts (fake) products and brand names. Less obvious is that Ramos, like Roy Lichtenstein, started off by exploring the ever expanding pantheon of American superheroes and cartoon characters, before delving into female nudity, as depicted in men’s magazines, girlie calendars and advertisements.

“Cigarettes aren’t really sexy, car parts aren’t normally sexy, or cheese,” said Schreiber.

“I have to continue with the idea of humor. Everything else is so depressing. Life is so depressing. Everybody’s being shot.”

But Ramos put it all together and revealed a trend in modern advertising (developing in the 1960s) of companies sexualizing their products by showing attractive women next to their products. What Ramos did was to exaggerate this by making the product bigger and display it next to nude women. This was very provocative at the time, and was also kind of Surrealistic.

“My work is rooted in Surrealism, definitely,” Ramos told Paul Karlstrom in a lengthy 1981 oral history interview, which is part of the Archives of American Art at the Smithsonian Institution. In it, Ramos comes across a quite down to earth character who is well versed in art history. As with the great Surrealist paintings, Ramos work is all about “conjunctions,” a combination of symbols that do not necessarily fit together. The difference is that the Surrealists were often more absurd: Salvador Dali’s melting watch or a man wearing a tuxedo walking in the desert.

In fact, Ramos cites Dali as his biggest influence, as it was a work by the Spanish master, “Soft Construction with Boiled Beans” which made him decide to become an artist in the first place. He was then about 16 years old. Interestingly, Ramos’ “girl-in-fruits” series was born out of a real life experience.

“I was working during summer school while I was going to college,” Ramos told Karlstrom. “And all of a sudden I see these guys come up in this truck and they dump this load of oranges in the grass. And out comes this girl in this white bathing suit with a little satin banner that said “Ventura County.” They kind of bury her halfway into this stuff and then take all these photographs to send back home for the papers to promote the orange fair. As I was sitting there, I said to myself: ‘that’s really surreal.’”

“A lot of artists want to do figure painting from some spiritual, mystical or emotional kind of position,” Ramos also said. “But I don’t see it that way. I’ve only used the figure in my work as iconography, that is to say, as depictions of contemporary iconography. If you look around at the media, the figure is used in a myriad of ways for various purposes, advertising, in the form of billboards or on TV, magazines, you know, all around the American landscape. My interest in the figure grows out of that kind of situation, that is to say, an external situation that interests me visually.”

Seeing Ramos’ liking and depictions of the female body, despite them (partly) being a critique on the use of women in advertising, it should not come as a surprisen that he has been attacked by the feminist movement. ”I tend to get the most flack from women who have flaws, who, as I see it, have visual flaws,” Ramos explained. “Women who have no flaws seem to enjoy my work.” His reply to such criticism tends to be short and sharp: “I paint pictures of women, not women.” A subtle reminder of Magritte who wrote under the image of a pipe: “Ceci ce n’est pas une pipe.”

Interestingly, many of the women depicted in Ramos’ paintings are based on the image of his wife, Leta. At first, she did not want him to paint other women in the nude, so the only alternative was that she herself would pose. Ramos would then paint different heads and faces. While Ramos is still painting naked women, Ramos and Leta are still happily married.

TEXT BY PETER SPEETJENS