PETROS CHRISOSTOMOU: THROUGH THE LOOKING GLASS

All is not what it may seem in the work of Petros Chrisostomou. The British artist meticulously sculpts strangely familiar miniature worlds … only to blow them out of proportion again with the simple click of a camera.

Petros, you are quite the global citizen: born in London, of Cypriote descent, living in NY. Could you tell us a bit about your journey?

Certainly. I would love to explain it as simply as possible. My mom was actually born in Cyprus as a British subject when it was under British rule before Cyprus gained its independence. She moved to London in the ’70s to have a better life with more opportunities. And I suppose also from fear that the rest of the island would be occupied after the Turkish invasion in 1974. So, I was born in London and grew up there and am very fortunate that I was able to have these metropolitan and cross-cultural experiences from the start.

A few years after graduating art school I was offered an opportunity to do an artist residency in New York which is what made me move there. Initially, it was supposed to be for one year only, but I ended up meeting someone and falling in love and decided to try and stay and make my future in New York, so that is how I ended up here for much longer!

Was art always the path ahead for you? Your childhood “I want to be an astronaut” dream? Or did this gradually take shape as you grew older?

I think because I grew up in a single-parent family and because my mom did not have the opportunity to study further than high school, she sort of encouraged me to do whatever I wanted which – when I think about it – was super risky, but also made me very lucky.

She also had a lot of time to engage with me, and we would build tree houses, or make costumes and all kinds of fantastical things. This is all before video games were available. So, I think I did not really have much distinction between the fantasy of being an astronaut or something else, because somehow I was able to live these experiences through making art. We would build caves and forts and space ships and all other such things, which sounds ridiculous when I think about it but it certainly led the way to my understanding that I could make this my life path.

I was always scribbling on walls and tearing away at furniture. I don't know how I was able to get away with it but I suppose I was just always directed to a piece of paper or a sketchbook to keep me contained, and I think it just grew from there.

St. Martins and the Royal Academy School: both renowned institutions in the UK. How did a “formal” education help you become an artist?

That is a really interesting question because I often wonder about how people perceive things and what we learn directly and also indirectly. Certainly, these were great experiences, without a doubt some of the most incredible years of my life, and I met the most incredible people that I would not have the opportunity to meet otherwise. So many artist friends and visiting critics that form part of my extended community. It was also bizarre. I remember having casual conversations with Sir Norman Foster in the RA and also with Sir Ian Holm when he would come into the school to wait for his wife afterlife drawing classes. I remember sitting opposite Stella McCartney in the St. Martins’ Library. It did not really dawn on me why there were paparazzi waiting outside, I guess she went there for some peace and quiet, and we were looking at each other but not saying a word, but somehow communicating through facial expression. Essentially, I realized these people were real people just like everybody else. To answer the question in a basic sense, it gave me the opportunity to think bigger. It offered me an insight into life. And the possibility to think outside my humble reality and to understand that it could be possible to make a living as an eccentric creative person. It really opened my eyes to a lot of possibilities outside of what my background could offer

Could you have succeeded without a normal education?

I’d like to say yes because I think where there is a will there is always a way. Although it would have certainly been different for sure!

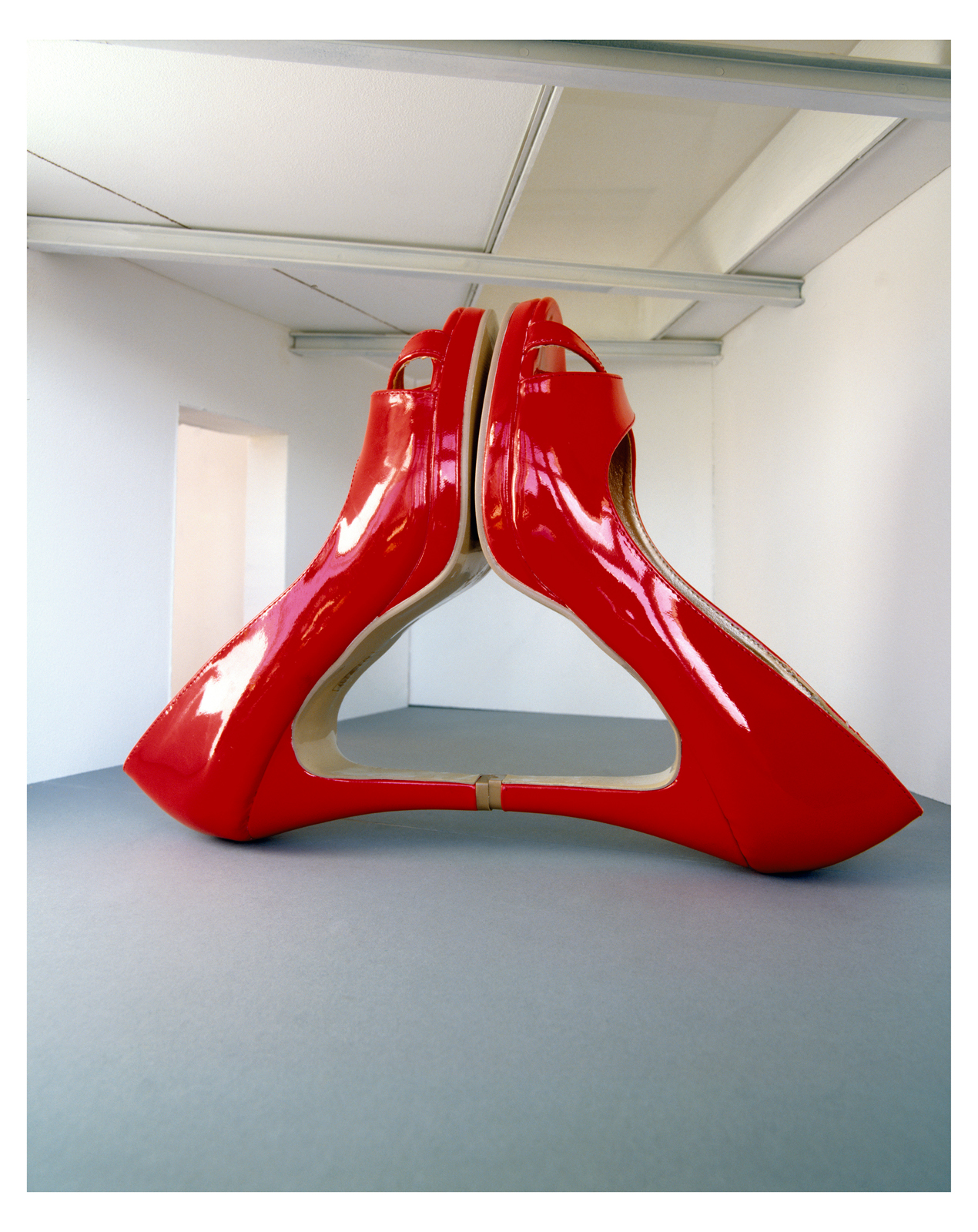

Many people will think of you as a photographer. But you are first of all a sculptor. In this day and age of the fast and the readymade, how important is the craftsmanship and the meticulous handwork to you and your work?

I’ll be honest: it is getting difficult because we do live in a culture where everything is so accelerated. With platforms like Instagram and many other social media outlets, we look at thousands of images every day, and often our attention span, or even our hunger and expectation to digest images, has distorted our relationship with reality. In a way, my work fits well as a critique to the digital age that we are experiencing. It somehow fits in so comfortably, and yet also goes against it, both at the same time. Whether it highlights issues related to this digital space that we are all starting to occupy, or whether it comments on the relevance of the human touch, and what the social or moral implications of that maybe, I feel that for my work I still do need to take the time to meticulously construct the scenes as a counterbalance to the moment we are in. Perhaps even just to reassure myself that I still exist. It is becoming so much more prevalent that humans will eventually become outmoded. Computers are starting to replace humans in the workplace more so than ever, to the point where creative and socially engaged practices will be at an even greater premium.

Obviously, there are the objects, the pens, shoes, hair, that take center stage. But I have the feeling the setting is as important. Could you tell us a bit more about the why, what and how of the settings you choose?

Of course. So, I want to describe a space by going through the physical motions of recreating it. Or rather what I want to do when I build these environments is to create a space for myself that I can claim as my own, and that I can express myself in.

In a way, these are safe spaces that I can identify with, within a bigger conversation of what it means to be present in the world around me. I know that may sound strange, or perhaps idealistic, but I always felt somehow excluded from the mainstream. Whether this is cultural or physical, I always identified with being the other. Growing up in Britain people would see me asGreek. In Greece, I would be seen as Cypriot, and in Cyprus, I was always the British guy. I never really knew where to exist.

In addition to this, the hierarchy of the gallery system, or the social class distinctions of being an immigrant in Britain were also factored into my decision to create my own domain. I started by creating my own galleries to exhibit and document my work and then moved onto other subjects that were autobiographical to recreate my childhood home and tell a story of my life. I then decided to create aspirational spaces of grandeur to contrast the realities of the domestic environments that I was building and create an interesting dichotomy between these different places and how my objects would respond to them, given the context that they were being seen in.

You are the first person ever to make me link high heels with Battlestar Galactica Spaceships and I will be forever grateful! So, what’s with the shoes?

Ha, ha! I actually get that question quite a lot! People seem to be perplexed by the shoes. They relate my work to some kind of psychosexual subconsciousness, which is not far from the truth I guess. Although what I should highlight is that I made this series of works after I returned from a residency in Beijing.

It related to seeing mass-produced items, specifically shoes, that were cheap and consumable, and relating these to the idea of the art object, to parody the idea of art as a consumable object in and of itself. The shoe is literally an item used to walk with, and I made these works also at a time when I made my first steps into the art world.

You first sculpt your work and you then turn it into an image. How and why did you first turn to photography, which compared to the first stage of your work is a relatively mechanical act? Why not present the sculptures as just that?

In terms of translating my objects into photographs, this started out of necessity and developed as a concept of my work. I used to make large scale installations with found objects as a way of making creative statements by occupying space. It then developed as I would need to document these works to have a record of their existence after they had been dismantled. And so then related this to the various famous artworks that we know through reproduction and image rather than physical representation, which formed the conceptual infrastructure of my work.

Funny thing is that relatively simple, “mechanical” photography allows you to play with scale and perspective, and turn "mini into maxi." Do you like playing with people’s minds?

Yes, I think I do. I like to distort perception and I use the scale as a way of doing this. I often give both sides of the story so that the viewer can be both grounded in reality but also transported to a make-believe place where they can draw their own conclusions.

How important is humor in your work/ life?

I think it is great if my work can provoke an emotive reaction in some way. If I am able to highlight some kind of absurdity within the system of objects and their given contexts, then that is a great result. In my life, I like humor too, it’s essential, and I also like to trade jokes, so if you know any good ones then please let me know!

What are you currently working on?

I am currently working on some more detailed versions of the generic gallery spaces and working with distinct raw materials. I like these because they are seemingly neutral spaces to experiment with, whilst also being an instantly recognizable backdrop for institutional critique.

I am working with some geometric forms and transparent plexi for my subjects in order to create a different type of balance within my photos. Previously there would be a background with a dominant object in the center of the composition that proposes a sort of question and answer relationship. While what is happening now is that I am trying to create more harmony in the overall image by using transparent material for my subjects to connect the space with the subject more closely.

Ever had the desire to create an Oldenburg- like larger than life statue “in the real”? Or maybe you already have?

Actually I have done, I started this around 2014 when I made a series of large earrings. The idea is that the earrings have an ornamental quality although they become abstracted to a minimalist primal form when blown up, which is a different feeling to the pop art aesthetic of the 60s. This work is a little unresolved for me at the moment, but I’m hoping to continue it and display the work at some point. The difference is that rather than try and replicate something as an object with its own autonomy, like an Oldenberg sculpture, I’m more concerned with these large objects as props within photographs of real spaces to continue with the existing concepts within my work that relate to our relationship with space

and constructed realities.

I won’t ask you what your main influences are, as arguably everybody does. But perhaps you can tell me about the one art exhibition or book that really blew you away in 2018?

I was visiting New York around December 2018 and I knew there was a Jannis Kounellisexhibition at Gavin Brown’s Enterprise, so I made it my mission to go see the show before it came down, and luckily I managed to catch it. The show was sensational, it really moved me. It was set up over three floors across the whole gallery and really responded well to the raw architecture of the space.

There was one work in particular on the top floor which is basically a whole wall covered in gold leaf, with what resembles the artist’s hat and coat hung in the center. And as you move closer you see the small flecks of gold fluttering slowly in the wind.

It really was something so beautiful and solemn, and at the same time sublime. I’ve been a fan of his work for quite some years and I met him in New York at the time of the show he had previously at the old space in Tribeca, where they reenacted the 1967 work with 12 horses led into the gallery space, and so it was very special to be able to follow up with him, sort of in a spiritual way.

What has 2019 brought or what will it bring Petros Chrisotomou?

I have some opportunities to travel back to Europe this year for some artist residencies, which are always a pleasure to do. I exhibited some new works in May, and then I have a residency lined up in Athens which I am very excited about because I have not been to Athens in about ten years.

I feel that Athens is very dear to me, as it was one of the first places that gave me a chance to exhibit my work, and so it feels in a way as if I will be returning to a homely place to see lots of old friends. I’m guessing a lot has changed since the last time I was there, but I am ready for the future and what it has in store.