FEATURE: TAKASHI MURAKAMI

TAKASHI MURAKAMI

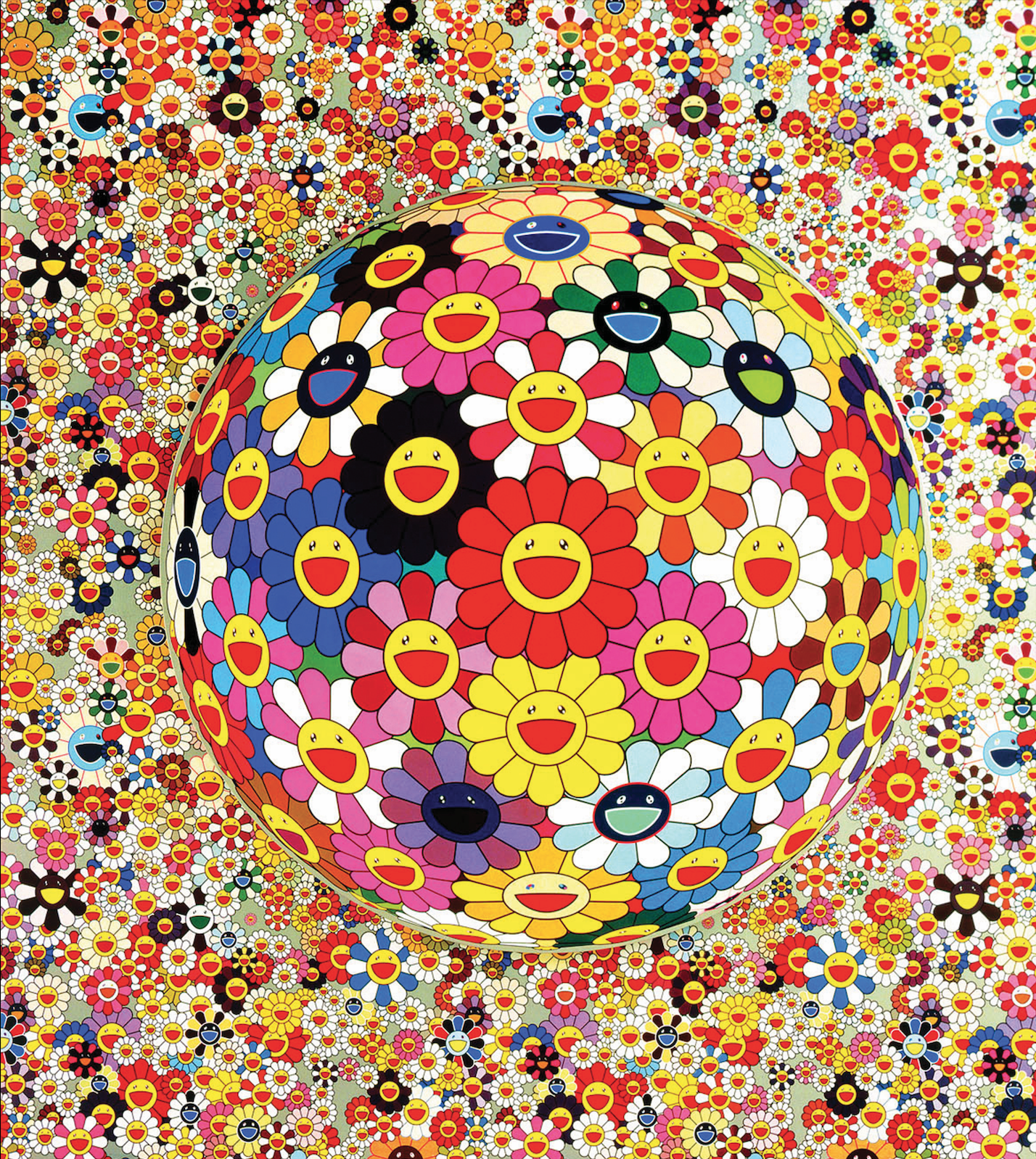

Stepping into the world of Japanese artist Takashi Murakami is like walking into a giant toy store. His sculpted and painted figures, with their rounded features and mushroom and flower companions, look like cartoon characters that ran off the pages of the latest manga adventure series. It is for that reason many people wonder if his work can be considered art. Murakami himself could not care less about how is work is perceived and defined. If there is one person in the world working hard to extinguish the distinctions between what is art and non-art, high art and low art, it is him.

“Many people wonder if his work can be considered art. Murakami himself could not care less.”

Now, admittedly, it is of course easier to take such a carefree position and ignore the Ivory Tower debate among the high priests of culture, when one sells everything from sculptures and paintings to printed t-shirts and fluffy cushions for millions of dollars annually. Commercially, Murakami is definitely more than an artist. He is an art factory. Or, as Mike Howe wrote in Wired Magazine: “He’s high art. He’s low culture. He’s a one-man mass market machine.”

Murakami himself once claimed that the Japanese do not really have a hierarchy between high and low art, while his work is “more about creating goods, and selling them, than about exhibitions.”

No wonder that his work is everywhere. It has been auctioned by Sotheby’s London, and is sold in every Japanese toy store. It adorns children’s bedrooms and executive board rooms, and was exhibited in leading art galleries and museums in Tokyo, LA, Boston and Bilbao.

Fashionistas will know Murakami for his collaboration with Marc Jacobs on a line of handbags for the Louis Vuitton fashion house, while literature lovers may wonder if he is somehow related to the bestselling author Haruki Murakami. Well, he is not. Finally, and for what it is worth, Murakami was the only artist to make it onto Time Magazine’s 2008 list of the 100 most influential people.

Seeing his work today, one may be surprised to learn that Murakami initially studied Nihanga, a traditional style of Japanese painting. When doing his PhD however, he grew increasingly disappointed with this 19th century art form, which he considered out of touch with the likes and preferences of modern day Japan, especially with the country’s overwhelming appetite for manga and anime.

And so, one day, he put his brush and easel aside and plunged into the big-eyed world of manga, producing his first major character, Mr. DOB, in 1993. Mr. DOB is a kind of balloon- shaped Mickey Mouse with big round eyes, and even bigger ears with the letters D and B in them. Mr. DOB has remained a major part of Murakami’s oeuvre ever since. He comes in all colors, and appears on paintings, t-shirts, key rings and balloons.

In 1997, he went on to produce Miss KO, a long-legged fiberglass mix between a nurse and a stewardess on fire-red high heels. One of his most talked about works is The Lonesome Cowboy (1998): a naked, spiky- haired young man holding his cock with one hand to produce a lightning bolt-like stream of sperm flying over his head. In 2008, it was sold by Sotheby’s London for $15 million.

Playing on the same theme, a pink-haired naked girl equipped with gigantic tits sprays milk in a lightning bolt around her body. In 2003, the Rockefeller Center in New York acquired a less controversial work known as Mr. Pointy, a fairytale-like figure with a pointy head flanked by four smaller figures on toad stools. It is all wonderfully colorful and sweet.

Not all of Murakami’s work is that playful and bright. He did for example a series on Daruma, a 6th century Indian monk who is considered the founding father of Zen Buddhism. Murakami portrays him as a dark, almost deranged figure with whirling eyes. Legend has it that Murakami meditated for nine years, without ever closing his eyes, before reaching enlightenment. In the process his arms and legs fell off.

He remains a popular figure in Japanese culture, where he is seen as a symbol of patience and endurance. The Daruma series illustrates how ancient Japanese themes and techniques are still present in Murakami’s, at first sight, very contemporary work.

Murakami has often been called Japan’s Andy Warhol. Like his illustrious American predecessor he mingles high and low art, and uses popular culture as a main inspiration. He is also nearly as self-promotional as the silver haired Pop Art maestro. And he works in a factory! Kaikai Kiri is an art-making collective or corporation based in a series of buildings in Tokyo known as the Hiropon Factory.

Yet there are differences as well. While Warhol’s factory was a hangout for the chic celebrity clique of New York City, the Hiropon Factory is really a factory, which produces around the clock and is home not only to dozens of young artists, but also accountants, managers and IT specialists. The factory’s treasure grove is its database filled with figures and decorative patterns, which can be modified, used and re- used over and over again. The drawing process starts traditionally, with a notebook, yet once a figure is finalized, it will be scanned, digitally mastered and colored.

It is the use of computers that allows Murakami and his team to produce sculptures and paintings that cost millions of dollars in galleries and museums, as well as re- productions and prints that sell for a few dollars in toy stores. That is another difference with Warhol, who did work on popular culture, yet only produced for the well-heeled. Murakami literally produces for everyone.

Finally, Murakami is also a curator, whose shows shed a light on his main motivations and sources of inspiration. In 2000, he organized an exhibition of Japanese art called Superflat, which focused on mass-produced entertainment and its effects on contemporary aesthetics. It was called as such for several reasons. Firstly, Japanese digital art often lacks perspective. Secondly, it says something about the aesthetics of the digital age. Thirdly, it refers to the rejection of high and low art.

In 2005, he curated Little Boy: The Arts of Japan’s Exploding Subculture, which showed dozens of anime and manga characters, and toys, as well as art works. It remains a particular feature of Japanese society, this overwhelming obsession with everything manga and anime, and which – let’s not forget – can be ultra-sweet, ultra- violent, or ultra-sexual.

Some think, including Murakami, that the WWII trauma and following US occupation have something to do with it: manga and anime as a kind of collective exercise in acting out. Hence the name Little Boy, which not only refers to kids and kids culture, but also to the A-bomb the Americans threw on Hiroshima after months of bombardments on Japan’s major cities.

For the world’s first A-bomb had a name: Little Boy.

TEXT BY PETER SPEETJENS