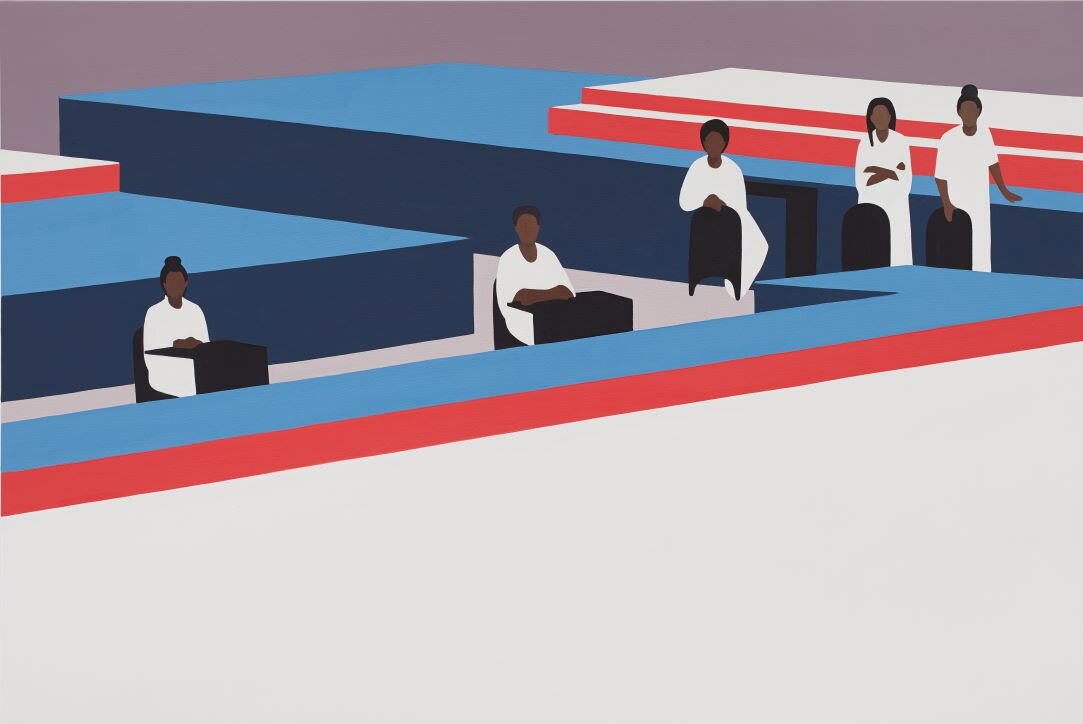

Thenjiwe Niki Nkosi - Power Dynamics & art

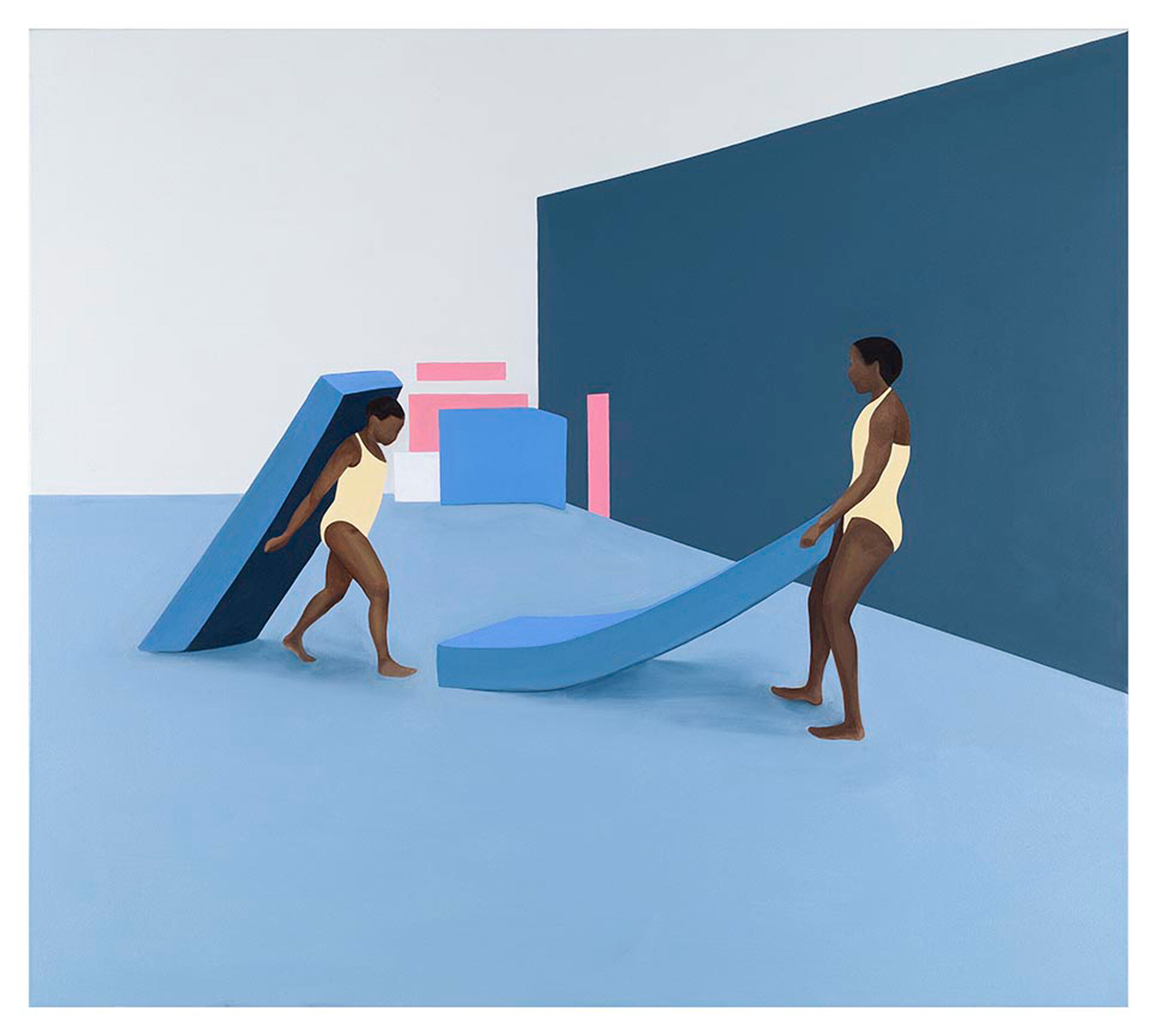

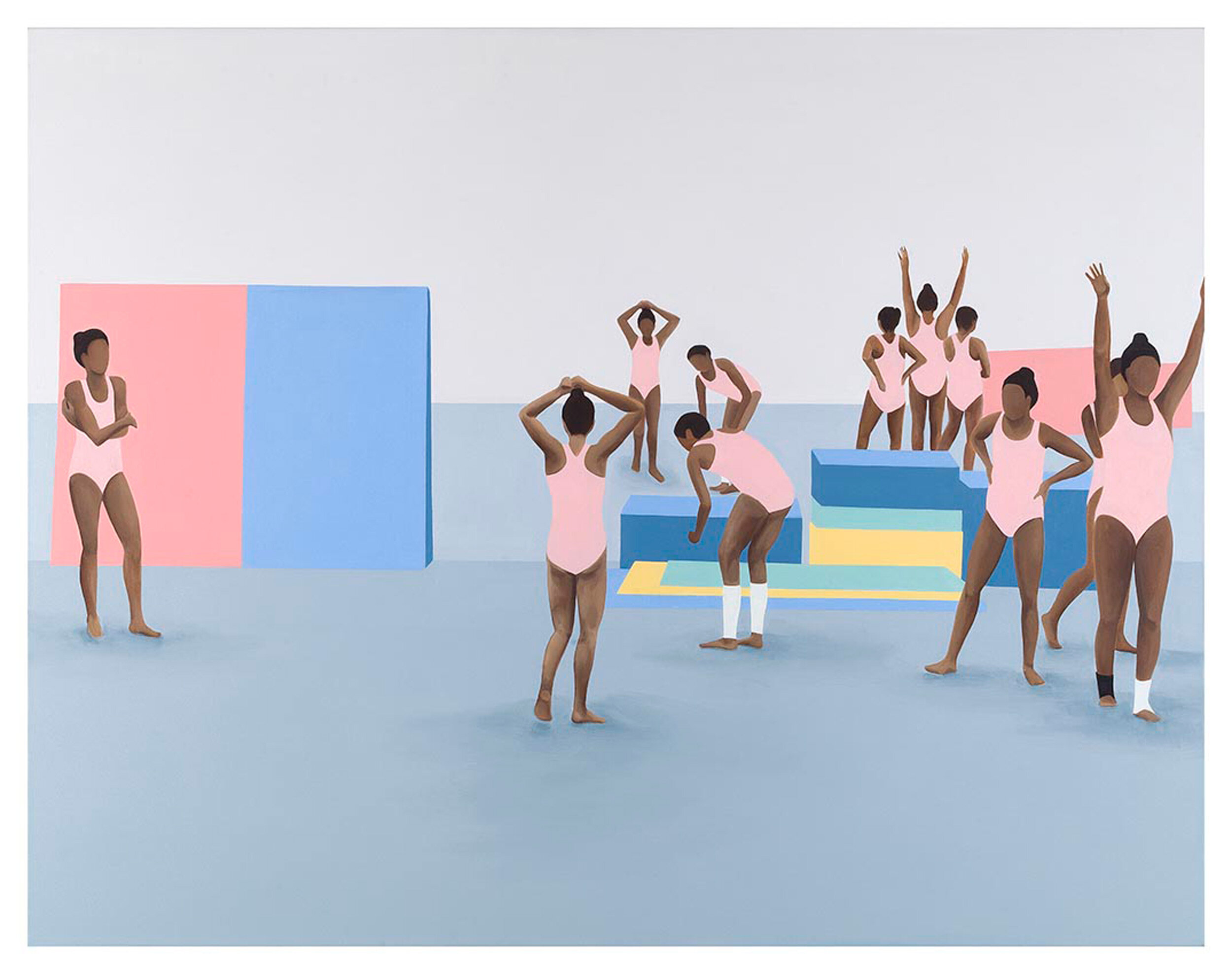

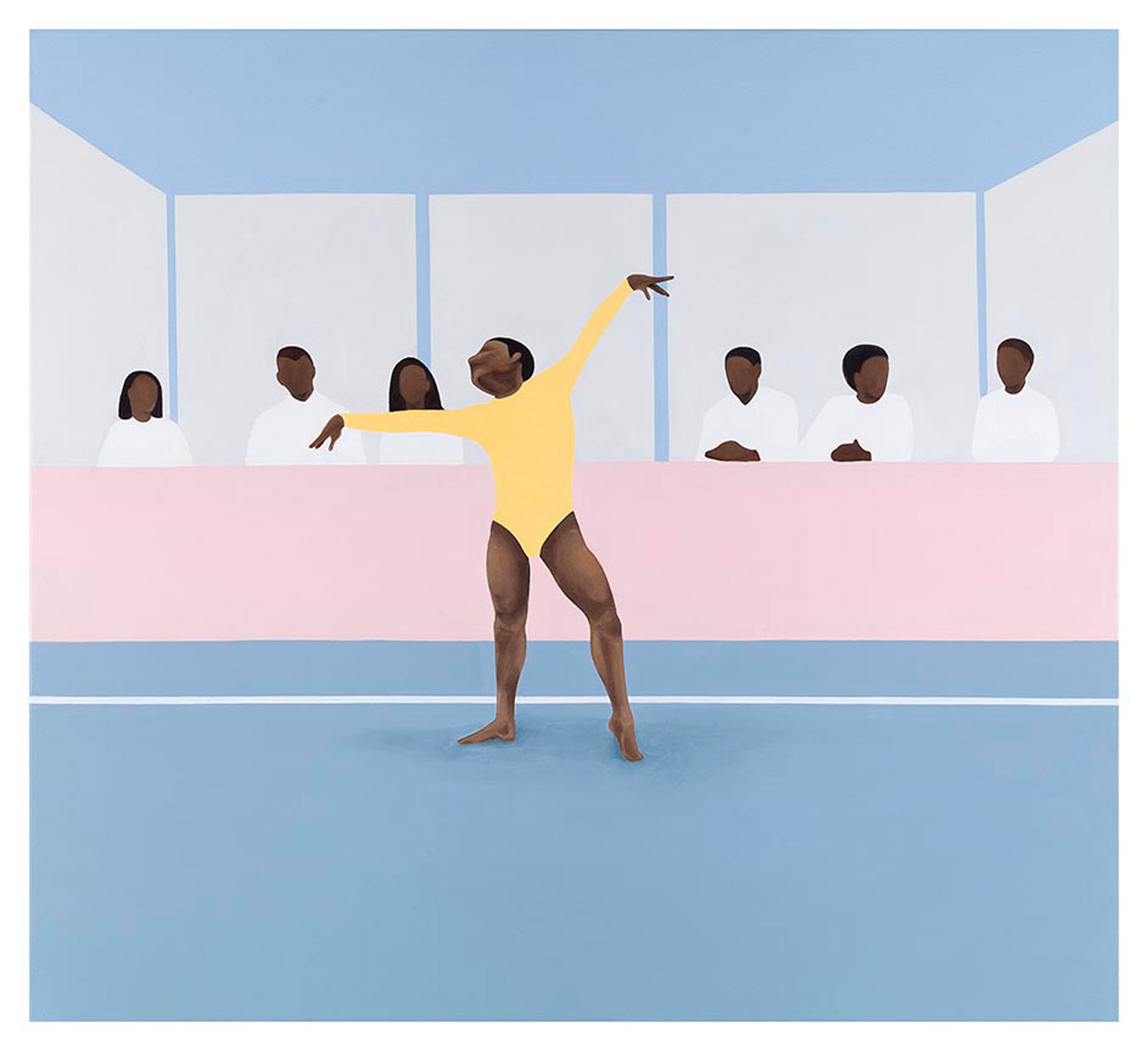

Her ethereal paintings exude power and liberation. Her work is sensitive, bold - yet stripped down to its utmost power. We had the pleasure to talk to the artist about her latest work, in which she explores the power dynamics inside a gymnasium.

Tell us a bit about you, the person behind the wonderful work we see:

I am a multimedia artist from South Africa and the United States. A lot of people think of me as a painter only, but really painting is just the medium that best fits my practice at the moment. I also work in drawing, photography, video. But right now painting has carved a meditative and contemplative space for me. It’s a solitary space to bring home all my ideas.

What is the main theme you’re exploring in your gymnasium series?

I think all my work deals with questions of power, and how structures of various kinds uphold power dynamics. In this series I’m thinking about the relationship between performer and audience, judges and other witnesses – and I’m interested in the power dynamics between all of them. Performance is a very vulnerable space to occupy, and I see a lot of links between the field of gymnastics and my personal journey as an artist. Navigating what it’s like to put work out there and have it subjected to so many interpretations. In a way, I am a performer myself – putting my work in the public realm for consideration and scrutiny.

The art world is dominated by white supremacy

Thenjiwe Niki Nkosi

What do power structures look like in a male dominated art world (87% of U.S museum collections are by male artists, and 85% of the artists are white)

The art world is a political structure. It remains dominated by white supremacy – a suffocating and excluding structure. We’re all navigating powerful, established structures and sometimes it’s about finding or creating one’s own space within those constructs, with determination and integrity. I’ve always wanted to be an artist on my own terms, and to have the consideration that white artists are afforded – where their work is considered first as work, without their identity being thrust upon readings of it. But now I think it’s rather that I want work by white artists to be read with the same awareness of identity and position as my work is read with. In either event, it will take the dismantling of white supremicist thinking for all our contributions as artists to be considered as part of a human history of art.

Your work gets a lot of attention on social media, how does getting online recognition change the way you perceive and produce your art?

It’s funny you ask this because I was just talking to my studio assistant who was making fun of me for being too inactive on social media. The truth is I am torn between seeing Instagram as a tool for reaching wide audiences and creating a sense of community, and on the other hand, being somewhat intrusive and overexposing.

It can be difficult for an artist to maintain their vulnerability and sensitivity – which can be important and generative spaces from which to make art – while at the same time pushing their work constantly into the unknown. Although social media can be debilitating for the artist, if they are not mindful and gentle with themselves, I also see it as an opportunity for changing the art world. The internet offers the potential for the democratization of art, and there is surely beauty and power in that.

How does being a parent affect your work?

I’m acutely aware of what world I’m imagining and projecting. Putting your work out there, projecting ideas into the world is a powerful thing to be doing, and I am more aware of that power than ever. I want to do right by my child. So I want to try to make art, and by extension, to make a world, that is going to hold and inspire this young person.

Anything you would like to say to our Plastik audience?

Have rigor, learn and work hard, but be gentle with yourself. Be gentle with yourself and with your spirit.

Interviewed by Philippe Ghabayen